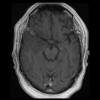

T1 + Contrast

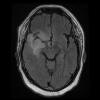

FLAIR

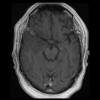

Ki67

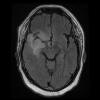

Ki67

| A 76 year-old man with a History of Parkinson

Disease, Sudden onset of Weakness with Tremor. January, 2020, Case 2001-1. Home Page |

Kar-Ming Fung, M.D., Ph.D. Last update: April 30, 2020.

Department of Pathology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Clinical information: The patient was a 76 year-old man with a history of Parkinson's disease. He developed sudden onset weakness of lower extremities while standing. He did not fall and was able to sit down. There was a brief tremor of his upper extremities but there was no seizure. On furhter work up, an enhancing mass, 2.0 x 1.6 cm, was noted in his right temporal pole. The mass was resected.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A. T1 + Contrast |

B. FLAIR |

C. | D. | E. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| F. | G. |

H. Ki67 |

I. Ki67 |

Radiology

of the Case: The mass is

located at the tip of the right temporal lobe causing minimal midline

shift. There is heterogensous enhancement suggestive of necrosis

(Panel

A).

There is substantial edema around this mass

with extension inot the posterior temporal lobe, insula, and inferior

lateral frontal lobe

Comment on

pathology: The rhabdoid area is

well-demarcated fromt he surrounding high-grade glioma with a pushing margin.

This phenomenon is most consistent with a high-grade/rhabdoid transfromation

arising from the surrounding high-grade glioma areas. This kind of

well-demarcated high-grade changes is more commonly seen in malignant/high-grade

transformation in sarcomas.

Molecular profile: A paraffin block containing the rhabdoid changes was

submitted for next generation sequencing and chromosome microarray testing.

Mutations:

TERT,

EGFR,

KRAS,

KDM61

Chromosomal abberations: +7, EGFR

amplification, CDKN2A/B homozygous deletion, and -10

MGMT promoter methylation: None

| DIAGNOSIS: Glioblastoma, WHO grade IV, IDH wild-type, with rhabdoid changes |

Discussion:

General Information

Pathology Rhabdoid

Changes Differential diagnosis

Related Interesting Cases

The prefix

rhabdo- is borrowed from Greek and it

means rod-like, rods, or wands. Perhaps it is a good way to describe the

striations in skeletal muscle, it is used to describe skeletal muscle type of

differentiation. Before the introduction of immunohistochemistry and molecular

biology, pathologists have to hunt for the striations the emulate striations of

skeletal muscle in a tumor in order to call it a rhabdomyosarcoma [click here to see a case]

or rhabdomyoma [click here to see a case].

In the modern practice, immunohistochemistry is typically employed to

demonstrate that there is no expression of desmin, myogenin, and MyoD for a cell

or tumor to be called rhabdoid.

Rhabdoid, on the other

hand, is a term used to describe cells that have features mimicking skeletal

differentiation but they are not they are not real skeletal differentiation.

Desmin, myogenin, MyoD and other skeletal muscle markers cannot be demonstrated

in these tumors. Rhabdoid cells are large polygonal cells with a large central

inclusion ultrastructrally composed of intermediate filament that is usually

vimentin. Nuclei are large, vesicular, with prominent nucleoli, and are

eccentric to the inclusion.

Primary rhabdoid tumors

constitute a group of predominantly pediatric tumors that have features

morphologically suspicious of skeletal muscle but without genuine skeletal

muscle phenotype. These tumors are mostly seen in kidney, in soft tissue and in

the central nervous system (atypical teratoid/rhabdoid) tumor. However they have

been described in virtually all of the anatomical sites. Most of these tumors

share the genetic signature of deletion of

SMARCB1 gene

(also known as hSNF5/INI1/BAF47)

on chromosome 22 with a small number of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors

associated with loss of BRG1 (SMARCA4) rather than

INI1. The protein product can be detected by immunohistochemistry

[Judkins AR, 2007]. Histologically,

epithelioid tumor cells have certain similarities with rhabdoid tumor cells.

Many epithelioid tumors are associated with loss of

INI1 expression [Hornick

JL et al., 2009].

Rhabdoid change, however, can be seen as a subpopulation of cells arising from a

histologically lower grade tumor [Perry

A et al., 2005,

Fung et al., 2004]. It is an indication of

malignant or high-grade transformation. It is essentially a growth pattern but

not a differentiation. It is typically not associated with loss of INI1

expression. Clinically, rhabdoid changes are typically associated with rapid

enlargement of a pre-existing tumor [Fung

KM et al., 2004]

and rapid clinical decline. These tumor are referred to composite rhabdoid

tumors and rhabdoid changes can occur in a wide variety of tumors.

Characteristically, no loss of INI1 is present in these composite rhabdoid

tumors [Perry A et al., 2005].

There a rare report of a glioblastoma with rhabdoid changes associated with loss

of INI1 in the rhabdoid component [Yamoto

J et al., 2011].

Rhabdoid glioblastoma

refers to tumor with rhabdoid cells arising within a background of otherwise

classic glioblastoma. It fits the definition of composite extra-renal rhabdoid

tumor. It should not be confused with epithelioid glioblastoma which is composed

of solid sheets of discohesive epithelioid cells without association with a

conventional glioblastoma component. Phenotypically, both rhabdoid and

epithelioid glioblastoma have intact INI1 and they are non-reactive for claudin

6 which is a marker for atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor

[Kleinschmidt-DeMasters

BK et al., 2010].

Both rhabdoid and epithelioid glioblastoma are more aggressive than conventional

glioblastoma [Sugimoto K et al., 2016].

Next generation sequencing panel study and chromosome microarray study were

performed in this case with a block containing the rhabdoid changes. There was

no loss of SMARCB1(INI1)

or SMAECA4(BRG1) were

demonstrated by next generation sequencing. Chromosomal changes included

gain of chromosome 7,

EGFR amplification,

CDKN2A/B homozygous deletion, and

heterozygous loss of chromosome 10. There was

also mutation of TERT promoter. These

features were classic for a glioblastoma. The rhabdoid changes stood out

distinctly in a background of high-grade glioma. The significant increase

in Ki67 labeling in the rhabdoid area. Both features supported that the rhabdoid

component was a high-grade transformation arising from the existing glioma. With

all of these features taken into consideration, this is a case of glioblastoma

with rhabdoid changes.

Glioblastoma with Rhabdoid Changes:

Glioblastoma, formerly

known as glioblastoma multiforme, has a reputation to demonstrate a wide range

of histopathologic patterns. In the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO)

classification of brain tumors, glioblastomas are separated into two major

groups, the IDH wild-type and

IDH mutant. In tumors with

IDH wild-type, there are several

patterns in addition to the classic pattern of high-grade glioma with

endothelial proliferation and, often, pseudopalisading necrosis. These patterns

include small cells and small cell glioblastoma, primitive neuronal cells and

glioblastoma with a primitive neuronal component, glioblastoma with

oligodendroglioma component, glioblastoma with gemistocystic astrocytic

components, glioblastoma with multinucleated giant cells, granular cells and

granular cell glioblastoma, lipidized clls and heavily lipidized glioblastoma,

and metaplastic glioblastoma.

In the 2016 WHO

classification, WHO also recognizes three rare variants namely epithelioid

glioblastoma, giant cell glioblastoma, and gliosarcoma. These variants typically

lack IDH mutation. Epithelioid glioblastoma is a characterized by mitotically

active, closely packed epithelioid cells and some rhabdoid cells with

microvascular proliferation and necrosis. Giant cell glioblastoma is

characterized by bizarre, multinucleated giant tumor cells and an occasionally

abundant reticulin network. Gliosarcoma is characterized by a biphasic pattern

with components demonstrating glial and mesenchymal differentiation.

Neither glioblastoma

with rhabdoid changes nor rhabdoid glioblastomas are recognized as a specific

pattern or variant in the 2016 WHO classification. Therefore, glioblastoma with

rhabdoid change (or component) is a better term than rhabdoid glioblastoma for

the current tumor which has both a conventional high grade glioma component and

a distinct subpopulation of rhabdoid tumor.

Yamamoto J et al.

described a similar case in 2012. Like other composite rhabdoid tumors, the

rhaboid component is signature of rapid growth. INI1 genes, like the current

case, is typically preserved [Perry A et al.,

2005,

Fuller CE et al.,

2001] but there are

exceptions [Donner LR et al., 2007,

Wyatt-Ashmead J et al., 2001].

Differential Diagnosis:

Epithelioid

glioblastoma: As mentioned earlier, epithelioid glioblastoma and

rhabdoid glioblastoma share some cytologic similarities. One can also imagine

that rhabdoid change is an exagerated version of epithelioid changes. However,

epithelioid glioblastoma is composed entirely of epithelioid cells while

rhabdoid glioblastoma contains rhabdoid areas embedded within a background of

conventional glioblastoma.

Metastatic rhabdoid carcinoma: In the personal experience of the

author, metastatic carcinoma with rhabdoid changes are rare biopsy specimens

fromt he brain. It is true that rhabdoid tumors are more aggressive and they

probably are more likely to metastasize. The speculation is that they would kill

the patient so fast that biopsy or resection of tumor in the brain are not

performed for many reasons. Anyway, metastatic rhabdoid carcinoma, however,

looks homogeneously rhabdoid which may be more suggestive of epithelioid

glioblastoma than rhabdoid glioblastoma. In addition, they can be multiple and

may have a positive history. Besides, they should be negative for glial

fibrillay acidic protein wile rhabdoid and epithelioid glioblastoma are

typically positive [Sugimoto K et al., 2016].

Atypical

teratoid/rhabdoid tumor [click

here to see a classic case]: This tumor occurs mostly in infants

under 3 years of age but uncommon in older children, and rare in young adults.

In contrast to its name, the degree of rhabdoid changes can vary from minimal to

fully developed. Most of them have loss of INI1 which can be demonsrated on

immunohistochemistry. But this is not full proof as a small number of them have

loss of BRG1. In coa ntrast to rhabdoid

glioblastoma, rhabdoid cells in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors do not form a

distinct area that stands out from the rest of the tumor. One must also note

that they can be positive for GFAP and which can be confused with rhabdoid or

epithelioid glioblastoma.

Metastatic

melanoma: Metastaic melanoma to the brain can appears as a

discohesive plasmacytoid or epithelioid tumor. These

tumors can, in fact, looks like a plasma cell tumor on cytologic preparation but

the nuclear grade is usually higher than that of a melanoma. Many of them are

amelanotic. However, metastatic melanoma will not be associated with a

conventional glioblastoma. On immunohistochemistry, melanoma are positive for

MART-1 (MelanA), tyrosinase, HMB45, and MiTF. These markers are

negative for glioma.

Related

Interesting Cases: