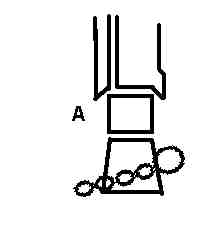

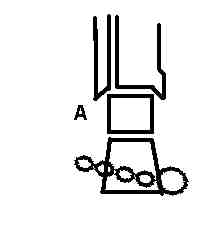

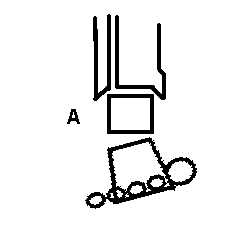

In uncompensated rearfoot varus (A), calcaneus (and forefoot) are inverted when the subtalar joint is neutral.

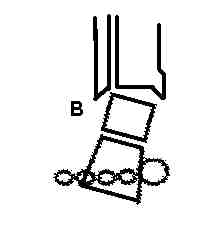

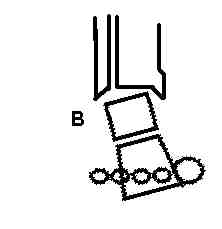

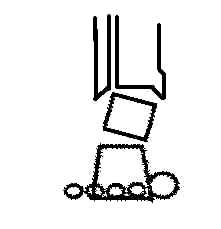

The person compensates (B) by pronating STJ to allow medial heel to touch the ground.

The compensation results in excessive pronation during loading response. The natural return to subtalar neutral during midstance and terminal stance is delayed.The therapist can eliminate the need for compensation by supporting the deformity using an orthosis with a medial heel wedge. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|