sternum, including xiphoid process, manubrium, sternoclavicular joint

clavicle

scapula, including

acromion process

the scapula's attachment to the clavicle at the acromioclavicular (AC) joint

supraspinous and infraspinous fossae

vertebral and axillary borders

inferior angle

coracoid process

humerus, including greater and lesser tubercles, intertubercular (bicipital) groove

Locate the coracoacromial ligament, the coracoclavicular and the coracohumeral ligaments.

Locate the sternoclavicular joint and the site of the costoclavicular ligament.

Is the scapular spine at the level of the T4 spinous process, a typical position?

Is the scapula's inferior angle at the level of the T8 spinous process, a typical position?

Is either scapula rotated? The base of the scapular spine and the scapula's inferior angle are typically aligned vertically.

Is one scapula more abducted or elevated than the other?

Is either scapula "winged?" Therapists generally attribute a winged scapula, one whose vertebral border rests away from the thorax, to an elongated serratus anterior. Investigate the attachments of the serratus anterior to see why elongation of this muscle permits the scapula's vertebral border to rest off of the ribcage.

If you detect scapular asymmetry in one of your lab partners, check the pelvic level to see whether the two findings are correlated.

|

|---|

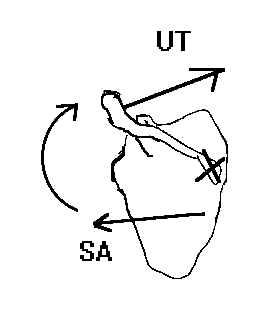

As your partner slowly elevates the shoulder through a "goniometric" arc of 180 degrees (using any combination of flexion and abduction), follow the scapula's upward rotation. Palpate two landmarks, the base of the scapular spine and the inferior angle, and note the following:

- The first 30 degrees of shoulder elevation involves largely glenohumeral movement. The scapula's movement is inconsistent. This is termed the setting phase.

- Thereafter, shoulder elevation involves an overall 2:1 ratio of glenohumeral to scapulothoracic movement.

What purposes does scapulohumeral rhythm serve?

Verify this fact by finding the muscles' lines of application and assessing their effect on an AP axis that projects through the sternoclavicular joint to the base of the scapular spine.

|

|---|

- middle trapezius

- lower trapezius

- rhomboideus major and minor

- levator scapulae

and predict each muscle's effect on scapular upward or downward rotation around the same AP axis that the previous problem specified.

Predict also each muscle's effect on causing the scapula to:

- elevate (move superiorly) or depress (move inferiorly).

- abduction (move away from the vertebral column) or adduct (move toward the vertebral column).