What is TTP?

It is hard to have an illness that neither you nor your family have ever heard of before. This information is written with the help of our patients, to help you understand what your doctor has told you.

TTP describes an illness for which the full name is too long to remember:

T is for Thrombotic, a term describing blood clots, which are called thrombi. In TTP, thrombi caused by clumps of platelets block small blood vessels. That can cause damage to organs such as the kidneys, heart, and brain.

T is for Thrombocytopenic, a term describing low platelet counts. Platelets are blood cells that are needed to stop bleeding. In TTP, they are used up in the abnormal clots that occur throughout the body.

P is for Purpura, a term describing the bruises and the small purple bleeding spots that are caused by too few platelets.

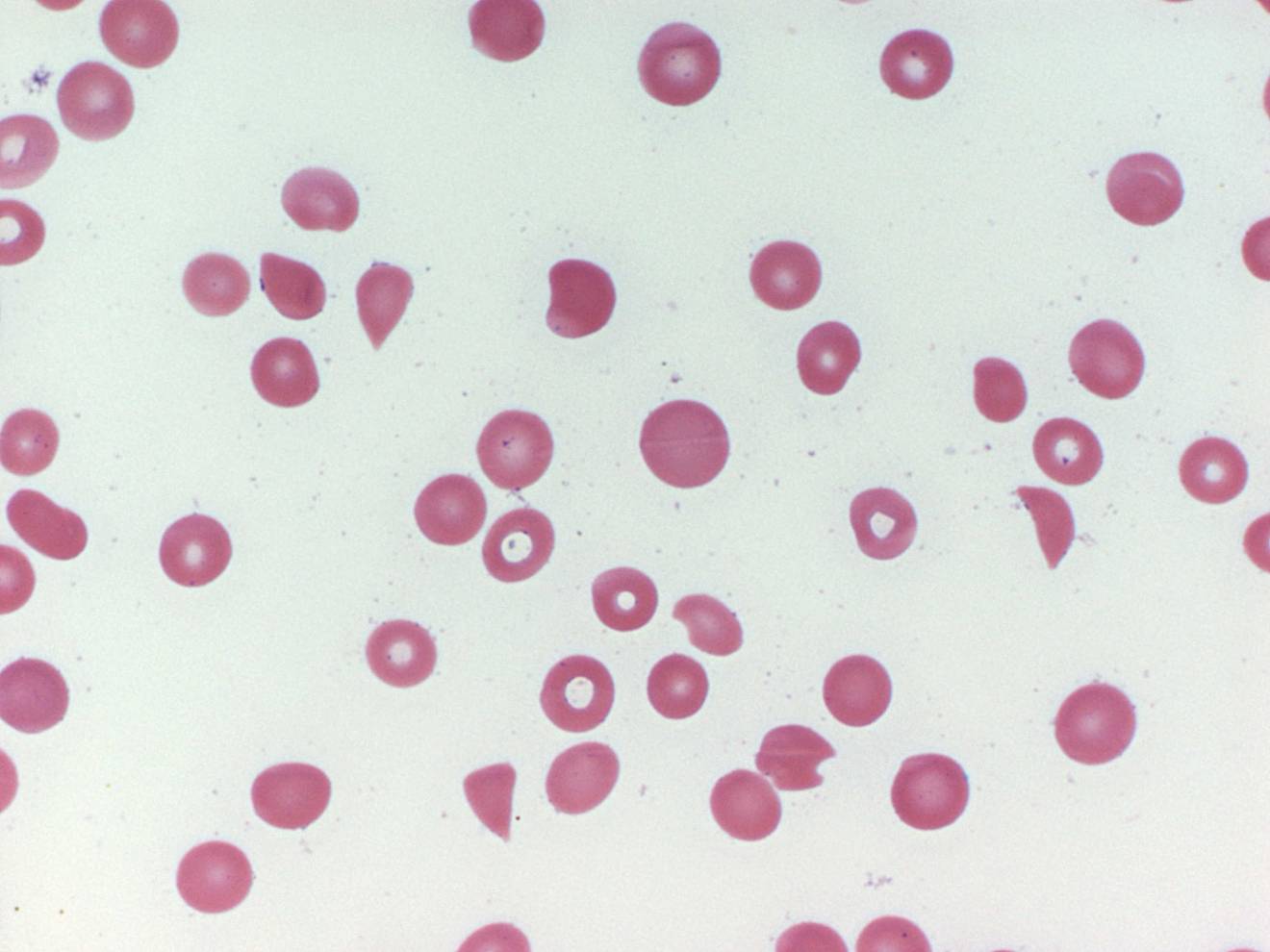

The picture below is a microscopic view of blood cells from a patient with TTP. Notice that there are no platelets. There should be 10 to 20 platelets in this picture, just like in the picture of normal blood cells. Notice the broken shapes of the red blood cells. Compare these cells to the normal red blood cells. This is the result of blood trying to flow through partially obstructed blood vessels. This picture is an important part of the diagnosis of TTP.

TTP was first recognized in 1924; in 1966 five key signs and symptoms were established: (1) thrombocytopenia, (2) hemolytic anemia, (3) kidney failure, (4) neurologic abnormalities (such as trouble with thinking or seeing, or actual stroke), and (5) fever. When these 5 problems occurred together, without an apparent cause, the “syndrome” of TTP was diagnosed. In that era almost all patients with TTP died. Beginning in the 1970s, plasma exchange (PEX) was first recognized as an effective treatment for TTP. In 1991, PEX was documented to be effective, with approximately 80% of patients surviving. Since 1991, PEX has become the standard treatment for TTP. (Plasma exchange treatment is described below.) This created urgency to make the diagnosis and to begin PEX. Now patients are diagnosed earlier in their disease. The diagnosis is often made only when a low blood platelet count and anemia is present, when there is no kidney failure, no neurologic abnormalities, and no fever. The old concept that all 5 clinical features had to be present to diagnose TTP is obsolete.

There is no laboratory test that clearly diagnoses TTP. Therefore we begin PEX as soon as we have strong suspicion. This means we begin treatment on some patients who may not have TTP. In some patients, another diagnosis, such as a serious infection, is diagnosed and then we stop plasma exchange treatments. However we continue to carefully follow all patients whom we have treated with PEX for a suspected diagnosis of TTP, including patients in whom another diagnosis was made. We do this by calling all of our former patients once a year. Long-term follow-up helps us to improve our diagnosis and treatment.

TTP is a disease of abnormal platelet clumping that obstructs blood circulation in small vessels. In the normal circulation, platelets move along the surface of blood vessels and don't stick to the vessel wall, or to each other, unless there is some injury to the vessel wall. As described below, patients with TTP are missing a key protein in the blood that helps to prevent platelet clumping.

Platelet clumping that obstructs circulation in the small blood vessels is the critical problem that occurs in TTP. These platelet clumps are called thrombi, described by the first “T” in TTP. Since the small blood vessels are similar in all the organs of our body, all parts of our body can be affected in TTP.

Click the following links for more details about TTP: